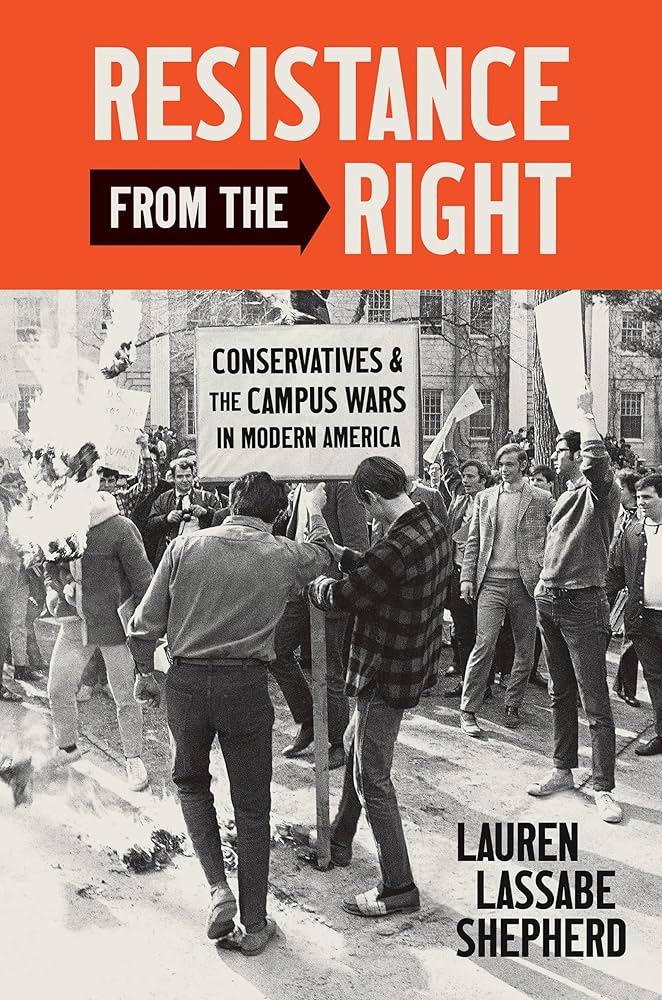

Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America by Lauren Lassabe Shepherd

In the ever-increasingly bifurcated world of American politics, Lassabe Shepherd’s monograph on the tactics of the conservative right to achieve a voice and influence on American college campuses is more than well-timed. This book uncovers the depth of today’s conservative/liberal divide, and while it focuses on the site of the university campus and highlights the actions of student organizations, bodies, and activists through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, it also brings to the fore the work of conservative academics who made these student-based activities possible. Emerging out of this history is the current network of conservative activists, academics, scholars, and strategies, their aim not much different than it had been, but accelerated and perfected: to amplify conservative values and ideology regardless of popular opinion, consensus among the student population or American population at large.

Lassabe’s argument, in essence, is layered: conservatives adopted the strategies of the liberal left for its own intentions and benefits with great success. In doing so, these conservative campus constituents undermined the efforts of the left and were able to achieve institutional and legislative changes favorable to their ideas. Over a period of decades, these conservative parties circumvented the majority — and largely liberal — voice, to ascend to a position of power and policy-making within the university and beyond it. Conservatives operated through and targeted their efforts towards institutional mechanisms to override liberal efforts and enact their values and ideologies in policy.

The book is divided into two parts, the first attends to “Coalition Building” and the ways in which campus conservatives found like-minded students, academics, and other supporters. In these chapters, Lassabe Shepherd reveals to the reader the ways in which conservatives adopted similar but oppositional signaling from the Liberal Left through sartorial means, appearance, and branding. In the second section, titled “Law, Order, and Punishment” chapters highlight the effects of the American War in Vietnam, the rise of Black Studies and other Ethnic Studies, or Area Studies departments in the university, as well the development of a network of conservative students, scholars, and external (to the university) supporters, many of whom entered the world of politics beyond the campus in the last decades of the 20th century; their work has contributed to the conservatism and its political strategies today.

The subject matter of Resistance From the Right indicates a clear target audience, though the monograph would be an immersive and revelatory read for most members of the educated public (liberal, conservative, or independent alike): that is, liberal scholars and educators in American academia today. Lassabe Shepherd answers a question most liberal scholars puzzle over, though it is never explicitly written in the book itself, and that is: Why and How did we end up with such conservative regulations, policies, and protocols when we seem to have such support for liberal values and ideas? Or, the more colloquial form, “What the H happened to us?” As universities continued to grapple with far right propaganda and groups on campuses, hate crimes and violence, racism, and classism, many administrators, faculty, and staff struggle to reconcile the diametrically opposed operations of their institutions with their own (typically liberal) perspectives.

Resistance From the Right is a necessary read for all American academics. It explains a lot.